In movies, time travel methods are mostly explained along the lines of "something something plutonium something wormhole." But physicists do have some idea of methods that might allow for actual time travel — though they might not necessarily prevent you from killing your own grandfather.

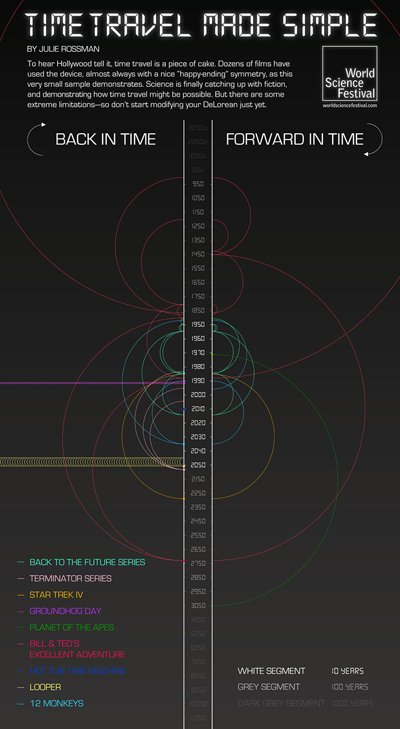

(World Science Festival: Is time travel possible?)

One trope in time travel science fiction is slightly plausible, if physically impossible — traveling faster than the speed of light. The crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise did this in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, by using the sun's gravitational pull to accelerate their spaceship to super-light speed. If it were possible to travel faster than light (Einstein calculated it would take an infinite amount of power), it is theoretically possible for signals to be sent back in time; it's questionable if the same method could work with people. Of course, if you have a faster-than-light ship, you could take a one-way trip into the future by taking advantage of the relativistic effects of time dilation: spend a few decades traveling, and arrive at your destination to find that centuries have passed since you left. In 2011, faster-than-light travel appeared closer to reality than ever; CERN scientists thought they'd found subatomic particles traveling faster than the speed of light. But the measurement was later found to be an error, possibly due to a faulty connection between a GPS unit and a computer.

(More from World Science Festival: Is the passage of time just an illusion?)

Wormholes are another possible route for traveling backwards and forwards through time. In the 1960s, New Zealand mathematician Roy Kerr calculated that a spinning black hole collapses not into a point, but into a ring; if something passed through this ring, it might travel through a tunnel in spacetime called an Einstein-Rosen bridge, or wormhole. The two ends of the wormhole might connect to different universes, or to different points in the same universe (separated by time as well as space). Scientists have yet to actually find evidence for wormholes, but they do square with Einstein's theories of gravity.

Frank Tipler, an astronomer, came up with another possible method of time travel that might work for actual space travelers, though building it is a bit of a tall order: First, you need a chunk of matter 10 times the mass of the sun. Then you roll it up into a cylinder, and set it spinning to a few billion rotations per minute. Stuff that travels in a precise spiral around the cylinder could end up on a closed timelike curve, a weird twist of spacetime that sends you on a loop back to the time where you entered it. But constructing one of these Tipler cylinders is going to take some time, as it has to be of infinite length.

(More from World Science Festival: How does the brain twist time?)

Assuming you make it back to the past, what happens if you kill an ancestor of yours? Do you cease to exist? Does you ceasing to exist then mean you don't go back in time in the first place to kill your grandfather? Russian physicist Igor Novikov developed a theory called the Self-Consistency Principle, under which the odds of any action that you might take creating a time paradox is basically zero. Changing the past is essentially physically impossible, just as you can't suddenly fly off the face of the Earth or suddenly turn into an elephant. Somehow, the universe balances the scales to keep the timeline in order. It's not clear exactly how this would work; perhaps if you set off to kill your grandfather in the past, you may find yourself waylaid by car problems, or a sudden illness. Or perhaps it's impossible to change the past because you've already been there in the past, taking actions that resulted in your future-present. Not all physicists (or philosophers, given the implications of Novikov's principle on free will) agree; some think that actions during time travel may create new timelines (as seen in Back to the Future II; for more on theories of alternate universes, check out the World Science Festival program "Multiverse: One Universe or Many?"). Whichever theory of timelines you subscribe to, it's probably best to play it safe and not kill anyone.

Time travel is one of my favorite topics! I wrote some time travel stories in junior high school that used a machine of my own invention to travel backwards in time, and I have continued to study this fascinating concept as the years have gone by.

We all travel in time. During the last year, I've moved forward one year and so have you. Another way to say that is that we travel in time at the rate of 1 hour per hour.

But the question is, can we travel in time faster or slower than "1 hour per hour"? Or can we actually travel backward in time, going back, say 2 hours per hour, or 10 or 100 years per hour?

It is mind-boggling to think about time travel. What if you went back in time and prevented your father and mother from meeting? You would prevent yourself from ever having been born! But then if you hadn't been born, you could not have gone back in time to prevent them from meeting.

The great 20th century scientist Albert Einstein developed a theory called Special Relativity. The ideas of Special Relativity are very hard to imagine because they aren't about what we experience in everyday life, but scientists have confirmed them. This theory says that space and time are really aspects of the same thing—space-time. There's a speed limit of 300,000 kilometers per second (or 186,000 miles per second) for anything that travels through space-time, and light always travels the speed limit through empty space.

Special Relativity also says that a surprising thing happens when you move through space-time, especially when your speed relative to other objects is close to the speed of light. Time goes slower for you than for the people you left behind. You won't notice this effect until you return to those stationary people.

Say you were 15 years old when you left Earth in a spacecraft traveling at about 99.5% of the speed of light (which is much faster than we can achieve now), and celebrated only five birthdays during your space voyage. When you get home at the age of 20, you would find that all your classmates were 65 years old, retired, and enjoying their grandchildren! Because time passed more slowly for you, you will have experienced only five years of life, while your classmates will have experienced a full 50 years.

So, if your journey began in 2003, it would have taken you only 5 years to travel to the year 2053, whereas it would have taken all of your friends 50 years. In a sense, this means you have been time traveling. This is a way of going to the future at a rate faster than 1 hour per hour.

Time travel of a sort also occurs for objects in gravitational fields. Einstein had another remarkable theory called General Relativity, which predicts that time passes more slowly for objects in gravitational fields (like here on Earth) than for objects far from such fields. So there are all kinds of space and time distortions near black holes, where the gravity can be very intense.

In the past few years, some scientists have used those distortions in space-time to think of possible ways time machines could work. Some like the idea of "worm holes," which may be shortcuts through space-time. This and other ideas are wonderfully interesting, but we don't know at this point whether they are possible for real objects. Still the ideas are based on good, solid science. In all time travel theories allowed by real science, there is no way a traveler can go back in time to before the time machine was built.

I am confident time travel into the future is possible, but we would need to develop some very advanced technology to do it. We could travel 10,000 years into the future and age only 1 year during that journey. However, such a trip would consume an extraordinary amount of energy. Time travel to the past is more difficult. We do not understand the science as well.

Actually, scientists and engineers who plan and operate some space missions must account for the time distortions that occur because of both General and Special Relativity. These effects are far too small to matter in most human terms or even over a human lifetime. However, very tiny fractions of a second do matter for the precise work necessary to fly spacecraft throughout the solar system.

Hello. My name is Stephen Hawking. Physicist, cosmologist and something of a dreamer. Although I cannot move and I have to speak through a computer, in my mind I am free. Free to explore the universe and ask the big questions, such as: is time travel possible? Can we open a portal to the past or find a shortcut to the future? Can we ultimately use the laws of nature to become masters of time itself?

Time travel was once considered scientific heresy. I used to avoid talking about it for fear of being labelled a crank. But these days I'm not so cautious. In fact, I'm more like the people who built Stonehenge. I'm obsessed by time. If I had a time machine I'd visit Marilyn Monroe in her prime or drop in on Galileo as he turned his telescope to the heavens. Perhaps I'd even travel to the end of the universe to find out how our whole cosmic story ends.

To see how this might be possible, we need to look at time as physicists do - at the fourth dimension. It's not as hard as it sounds. Every attentive schoolchild knows that all physical objects, even me in my chair, exist in three dimensions. Everything has a width and a height and a length.

But there is another kind of length, a length in time. While a human may survive for 80 years, the stones at Stonehenge, for instance, have stood around for thousands of years. And the solar system will last for billions of years. Everything has a length in time as well as space. Travelling in time means travelling through this fourth dimension.

To see what that means, let's imagine we're doing a bit of normal, everyday car travel. Drive in a straight line and you're travelling in one dimension. Turn right or left and you add the second dimension. Drive up or down a twisty mountain road and that adds height, so that's travelling in all three dimensions. But how on Earth do we travel in time? How do we find a path through the fourth dimension?

Let's indulge in a little science fiction for a moment. Time travel movies often feature a vast, energy-hungry machine. The machine creates a path through the fourth dimension, a tunnel through time. A time traveller, a brave, perhaps foolhardy individual, prepared for who knows what, steps into the time tunnel and emerges who knows when. The concept may be far-fetched, and the reality may be very different from this, but the idea itself is not so crazy.

Physicists have been thinking about tunnels in time too, but we come at it from a different angle. We wonder if portals to the past or the future could ever be possible within the laws of nature. As it turns out, we think they are. What's more, we've even given them a name: wormholes. The truth is that wormholes are all around us, only they're too small to see. Wormholes are very tiny. They occur in nooks and crannies in space and time. You might find it a tough concept, but stay with me.

Nothing is flat or solid. If you look closely enough at anything you'll find holes and wrinkles in it. It's a basic physical principle, and it even applies to time. Even something as smooth as a pool ball has tiny crevices, wrinkles and voids. Now it's easy to show that this is true in the first three dimensions. But trust me, it's also true of the fourth dimension. There are tiny crevices, wrinkles and voids in time. Down at the smallest of scales, smaller even than molecules, smaller than atoms, we get to a place called the quantum foam. This is where wormholes exist. Tiny tunnels or shortcuts through space and time constantly form, disappear, and reform within this quantum world. And they actually link two separate places and two different times.

Unfortunately, these real-life time tunnels are just a billion-trillion-trillionths of a centimetre across. Way too small for a human to pass through - but here's where the notion of wormhole time machines is leading. Some scientists think it may be possible to capture a wormhole and enlarge it many trillions of times to make it big enough for a human or even a spaceship to enter.

Given enough power and advanced technology, perhaps a giant wormhole could even be constructed in space. I'm not saying it can be done, but if it could be, it would be a truly remarkable device. One end could be here near Earth, and the other far, far away, near some distant planet.

Theoretically, a time tunnel or wormhole could do even more than take us to other planets. If both ends were in the same place, and separated by time instead of distance, a ship could fly in and come out still near Earth, but in the distant past. Maybe dinosaurs would witness the ship coming in for a landing.

Now, I realise that thinking in four dimensions is not easy, and that wormholes are a tricky concept to wrap your head around, but hang in there. I've thought up a simple experiment that could reveal if human time travel through a wormhole is possible now, or even in the future. I like simple experiments, and champagne.

So I've combined two of my favourite things to see if time travel from the future to the past is possible.

Let's imagine I'm throwing a party, a welcome reception for future time travellers. But there's a twist. I'm not letting anyone know about it until after the party has happened. I've drawn up an invitation giving the exact coordinates in time and space. I am hoping copies of it, in one form or another, will be around for many thousands of years. Maybe one day someone living in the future will find the information on the invitation and use a wormhole time machine to come back to my party, proving that time travel will, one day, be possible.

In the meantime, my time traveller guests should be arriving any moment now. Five, four, three, two, one. But as I say this, no one has arrived. What a shame. I was hoping at least a future Miss Universe was going to step through the door. So why didn't the experiment work? One of the reasons might be because of a well-known problem with time travel to the past, the problem of what we call paradoxes.

Paradoxes are fun to think about. The most famous one is usually called the Grandfather paradox. I have a new, simpler version I call the Mad Scientist paradox.

I don't like the way scientists in movies are often described as mad, but in this case, it's true. This chap is determined to create a paradox, even if it costs him his life. Imagine, somehow, he's built a wormhole, a time tunnel that stretches just one minute into the past.

Through the wormhole, the scientist can see himself as he was one minute ago. But what if our scientist uses the wormhole to shoot his earlier self? He's now dead. So who fired the shot? It's a paradox. It just doesn't make sense. It's the sort of situation that gives cosmologists nightmares.

This kind of time machine would violate a fundamental rule that governs the entire universe - that causes happen before effects, and never the other way around. I believe things can't make themselves impossible. If they could then there'd be nothing to stop the whole universe from descending into chaos. So I think something will always happen that prevents the paradox. Somehow there must be a reason why our scientist will never find himself in a situation where he could shoot himself. And in this case, I'm sorry to say, the wormhole itself is the problem.

In the end, I think a wormhole like this one can't exist. And the reason for that is feedback. If you've ever been to a rock gig, you'll probably recognise this screeching noise. It's feedback. What causes it is simple. Sound enters the microphone. It's transmitted along the wires, made louder by the amplifier, and comes out at the speakers. But if too much of the sound from the speakers goes back into the mic it goes around and around in a loop getting louder each time. If no one stops it, feedback can destroy the sound system.

The same thing will happen with a wormhole, only with radiation instead of sound. As soon as the wormhole expands, natural radiation will enter it, and end up in a loop. The feedback will become so strong it destroys the wormhole. So although tiny wormholes do exist, and it may be possible to inflate one some day, it won't last long enough to be of use as a time machine. That's the real reason no one could come back in time to my party.

Any kind of time travel to the past through wormholes or any other method is probably impossible, otherwise paradoxes would occur. So sadly, it looks like time travel to the past is never going to happen. A disappointment for dinosaur hunters and a relief for historians.

But the story's not over yet. This doesn't make all time travel impossible. I do believe in time travel. Time travel to the future. Time flows like a river and it seems as if each of us is carried relentlessly along by time's current. But time is like a river in another way. It flows at different speeds in different places and that is the key to travelling into the future. This idea was first proposed by Albert Einstein over 100 years ago. He realised that there should be places where time slows down, and others where time speeds up. He was absolutely right. And the proof is right above our heads. Up in space.

This is the Global Positioning System, or GPS. A network of satellites is in orbit around Earth. The satellites make satellite navigation possible. But they also reveal that time runs faster in space than it does down on Earth. Inside each spacecraft is a very precise clock. But despite being so accurate, they all gain around a third of a billionth of a second every day. The system has to correct for the drift, otherwise that tiny difference would upset the whole system, causing every GPS device on Earth to go out by about six miles a day. You can just imagine the mayhem that that would cause.

The problem doesn't lie with the clocks. They run fast because time itself runs faster in space than it does down below. And the reason for this extraordinary effect is the mass of the Earth. Einstein realised that matter drags on time and slows it down like the slow part of a river. The heavier the object, the more it drags on time. And this startling reality is what opens the door to the possibility of time travel to the future.

Right in the centre of the Milky Way, 26,000 light years from us, lies the heaviest object in the galaxy. It is a supermassive black hole containing the mass of four million suns crushed down into a single point by its own gravity. The closer you get to the black hole, the stronger the gravity. Get really close and not even light can escape. A black hole like this one has a dramatic effect on time, slowing it down far more than anything else in the galaxy. That makes it a natural time machine.

I like to imagine how a spaceship might be able to take advantage of this phenomenon, by orbiting it. If a space agency were controlling the mission from Earth they'd observe that each full orbit took 16 minutes. But for the brave people on board, close to this massive object, time would be slowed down. And here the effect would be far more extreme than the gravitational pull of Earth. The crew's time would be slowed down by half. For every 16-minute orbit, they'd only experience eight minutes of

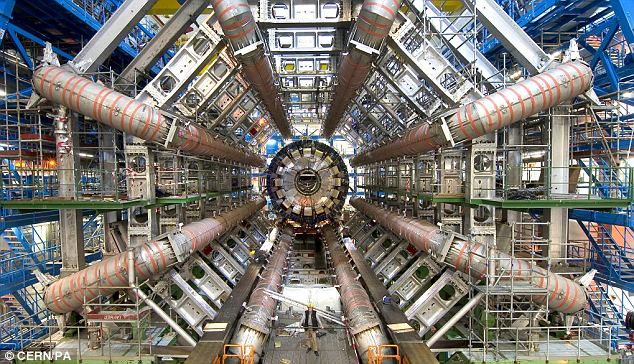

Inside the Large Hadron Collider

Around and around they'd go, experiencing just half the time of everyone far away from the black hole. The ship and its crew would be travelling through time. Imagine they circled the black hole for five of their years. Ten years would pass elsewhere. When they got home, everyone on Earth would have aged five years more than they had.

So a supermassive black hole is a time machine. But of course, it's not exactly practical. It has advantages over wormholes in that it doesn't provoke paradoxes. Plus it won't destroy itself in a flash of feedback. But it's pretty dangerous. It's a long way away and it doesn't even take us very far into the future. Fortunately there is another way to travel in time. And this represents our last and best hope of building a real time machine.

You just have to travel very, very fast. Much faster even than the speed required to avoid being sucked into a black hole. This is due to another strange fact about the universe. There's a cosmic speed limit, 186,000 miles per second, also known as the speed of light. Nothing can exceed that speed. It's one of the best established principles in science. Believe it or not, travelling at near the speed of light transports you to the future.

To explain why, let's dream up a science-fiction transportation system. Imagine a track that goes right around Earth, a track for a superfast train. We're going to use this imaginary train to get as close as possible to the speed of light and see how it becomes a time machine. On board are passengers with a one-way ticket to the future. The train begins to accelerate, faster and faster. Soon it's circling the Earth over and over again.

To approach the speed of light means circling the Earth pretty fast. Seven times a second. But no matter how much power the train has, it can never quite reach the speed of light, since the laws of physics forbid it. Instead, let's say it gets close, just shy of that ultimate speed. Now something extraordinary happens. Time starts flowing slowly on board relative to the rest of the world, just like near the black hole, only more so. Everything on the train is in slow motion.

This happens to protect the speed limit, and it's not hard to see why. Imagine a child running forwards up the train. Her forward speed is added to the speed of the train, so couldn't she break the speed limit simply by accident? The answer is no. The laws of nature prevent the possibility by slowing down time onboard.

Now she can't run fast enough to break the limit. Time will always slow down just enough to protect the speed limit. And from that fact comes the possibility of travelling many years into the future.

Imagine that the train left the station on January 1, 2050. It circles Earth over and over again for 100 years before finally coming to a halt on New Year's Day, 2150. The passengers will have only lived one week because time is slowed down that much inside the train. When they got out they'd find a very different world from the one they'd left. In one week they'd have travelled 100 years into the future. Of course, building a train that could reach such a speed is quite impossible. But we have built something very like the train at the world's largest particle accelerator at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland.

Deep underground, in a circular tunnel 16 miles long, is a stream of trillions of tiny particles. When the power is turned on they accelerate from zero to 60,000mph in a fraction of a second. Increase the power and the particles go faster and faster, until they're whizzing around the tunnel 11,000 times a second, which is almost the speed of light. But just like the train, they never quite reach that ultimate speed. They can only get to 99.99 per cent of the limit. When that happens, they too start to travel in time. We know this because of some extremely short-lived particles, called pi-mesons. Ordinarily, they disintegrate after just 25 billionths of a second. But when they are accelerated to near-light speed they last 30 times longer.

It really is that simple. If we want to travel into the future, we just need to go fast. Really fast. And I think the only way we're ever likely to do that is by going into space. The fastest manned vehicle in history was Apollo 10. It reached 25,000mph. But to travel in time we'll have to go more than 2,000 times faster. And to do that we'd need a much bigger ship, a truly enormous machine. The ship would have to be big enough to carry a huge amount of fuel, enough to accelerate it to nearly the speed of light. Getting to just beneath the cosmic speed limit would require six whole years at full power.

The initial acceleration would be gentle because the ship would be so big and heavy. But gradually it would pick up speed and soon would be covering massive distances. In one week it would have reached the outer planets. After two years it would reach half-light speed and be far outside our solar system. Two years later it would be travelling at 90 per cent of the speed of light. Around 30 trillion miles away from Earth, and four years after launch, the ship would begin to travel in time. For every hour of time on the ship, two would pass on Earth. A similar situation to the spaceship that orbited the massive black hole.

After another two years of full thrust the ship would reach its top speed, 99 per cent of the speed of light. At this speed, a single day on board is a whole year of Earth time. Our ship would be truly flying into the future.

The slowing of time has another benefit. It means we could, in theory, travel extraordinary distances within one lifetime. A trip to the edge of the galaxy would take just 80 years. But the real wonder of our journey is that it reveals just how strange the universe is. It's a universe where time runs at different rates in different places. Where tiny wormholes exist all around us. And where, ultimately, we might use our understanding of physics to become true voyagers through the fourth dimension

It's a common trope in science-fiction novels: Astronauts travel back in time by zooming through space at speeds faster than light (usually getting into trouble in the process).

Most physicists think that scenario is impossible.

But let's suspend disbelief for a second. If it time travel like this were possible, how exactly would it work?

It's a common trope in science-fiction novels: Astronauts travel back in time by zooming through space at speeds faster than light (usually getting into trouble in the process).

Most physicists think that scenario is impossible.

But let's suspend disbelief for a second. If it time travel like this were possible, how exactly would it work?

It turns out that objects traveling faster than the speed of light could go back in time — but in the process, a pair of phantom doubles of the speedy object would pop out of thin air, and one would then go backwards and be annihilated with another, according to one hypothesis, which Robert Nemiroff, a physicist at Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Michigan, described in a paper published in May in the preprint journal arXiv.

But don't stock up on plutonium for your DeLorean just yet. The new thought experiment is probably impossible, Nemiroff said.

"I don't believe you can create a spaceship that can go faster than light," Nemiroff told Live Science.

Faster than light?

Everyone has heard it: Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity means that nothing can travel faster than light in a vacuum. That's not quite true, though: Such speeds are technically possible, but relativity dictates that anything with mass becomes heavier as it zips faster and faster, so reaching and surpassing the speed of light would take infinite energy. (Weirdly, the math would also dictate that objects could be traveling faster than the speed of light, but could not slow down to below the speed of light, Nemiroff said.)

"It is just generally believed — and I mean generally to mean almost all physicists — that there is nothing that can travel faster than light," said Sabine Hossenfelder, a theoretical physicist at Nordita in Stockholm, Sweden, who blogs at BackReaction but was not involved in the current study.

And while physicists can send subatomic particles called muons forward through time, the issue with backward time travel is causality.

Time has an arrow, and that arrow points forward. Without this safeguard, all sorts of absurd situations can occur, such as the so-called grandfather paradox, the plot device in "Back to the Future" and several other sci-fi films. If you go back in time and kill your grandfather before he has your dad, how would you exist to go back in time in the first place?

But oddly, neither special relativity nor particle physics has a time orientation. In fact, antiparticles, the antimatter partners of regular particles, can be interpreted as either antimatter particles going forward in time or real particles traveling back in time, Hossenfelder said. And the equations of special relativity mean that an object going faster than the speed of light would travel backward in time, she added.

Spaceship doppelganger

To understand the implications of relativistic backward time travel, Nemiroff ran the numbers for a very simple case. In his thought experiment, a spaceship would start on a launching pad on Earth, travel at five times the speed of light to a planet about 10 light-years away, then turn around to return home to a landing pad not far from the liftoff site. (Other proposed methods of time travel, such as traveling through a wormhole in curved space-time, were not addressed in the study.)

It turned out that a pair of ghost-ships, one with negative mass and one with positive mass, the researchers speculate, must appear out of thin air.

Five years after embarking, Earthlings would see a very strange apparition: Because the light from the spaceship travels slower than the spaceship itself, after the vessel returned and sat on the landing pad, Earthlings would see images of the spaceship on its way out and another doppelganger spaceship on its way back.

Eight years later, things would look even odder: An image of the spaceship sitting on the landing pad would still be visible, as would two images (perhaps like holograms) of the spaceship on its outbound and return flights. Only this time, both of those images would look farther away, as if the spaceship was traveling backward in time.

Finally, after a bit more than 10 years, the phantom spaceship pairs would annihilate each other and you'd be left with the spaceship sitting on the landing pad.

The thought experiment prompts a lot of questions. How would it all work? What would the twin spaceships be made of? Which spaceship would be the "real one? Would the phenomenon work through the quantum behavior of entangled particles? And what would the people on the spaceships be doing? Nemiroff said he can't answer those questions, and he doubts it's possible in any case.

"It doesn't make a lot of sense, and I doubt if you would look at it microscopically it would actually be possible," Hossenfelder told Live Science.

Still, the study is extremely valuable as a teaching tool, Hossenfelder said.

Real-life pair production

The time travel, pair production would be similar to an established phenomenon that occurs in illumination fronts, Nemiroff said.

"There are things that go faster than light, like shadows on the wall," Nemiroff told Live Science.

To understand illumination fronts, consider this thought experiment: If you were to aim a laser pointer at the moon (and assuming that atmospheric effects, clouds, buildings, etc. did not block the light), you would only have to flick your wrist from one side of the moon to the other faster than about 4 seconds to have the dot of light travel faster than light, Nemiroff said. If you had a powerful enough laser, an ability to take fast, time lapse-photography and an awesome telescope, you would see a pair of spots, slightly separated in distance, on the moon's surface, he said.

The trick is that in this scenario, what's traveling faster than the speed of light is not information, because there's no way for a person on one side of the moon to transmit information superluminally to the other spot via the illumination front, Nemiroff added.

Copyright © 2011 - All Rights Reserved - Softron.in

Template by Softron Technology